Years ago, I heard somebody say that music is the envy of all other art: it’s the one that reaches us first. You’re 46 with a bad back, but suddenly, because of a song, you’re on the edge of seventeen again and Steve Nicks is snarling, The clouds never expect it when it rains. Then it ends and your back still stings.

As a kid, I listened to The Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band on a hybrid record-radio player whose only station I could find was Smooth Jazz 105.9, which kept asking what’s love got to do with it.

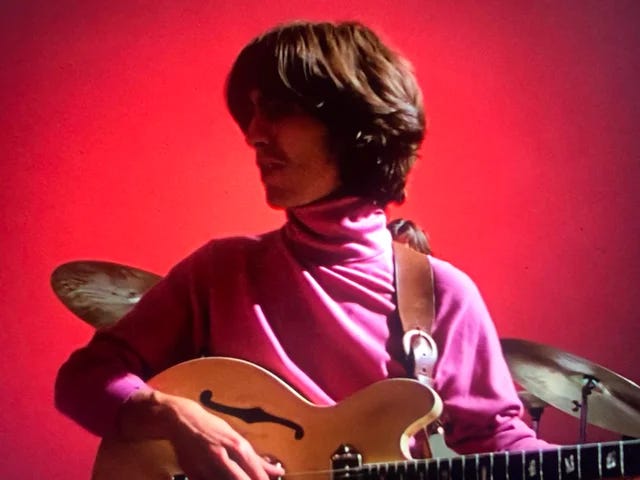

My parents, born in the 1950s, each had a Beatle: my father, George Harrison; my mother, John Lennon. My sister, not born in the 1950s, had eyes only for Paul McCartney. I liked George because people called him quiet, and that’s what people called me too.

As for Ringo: I sincerely hope one of the dogs claimed him.

Invariably, there’s one reason that drags me back to an album: nostalgia. It’s a feeling that is, at least for me, inextricably tied to innocence. I want to understand the world as I did then, as an illusion whose boundaries were only as wide as my own.

Recently, I started relistening to Harry Styles’s 2017 album, his first as a solo artist since leaving One Direction. The album, also called Harry Styles, features a moody, glistening shot of Styles’ back as the cover art. This is vulnerable! it shouts. You know less than you think you do! (A message to One Direction fans?)

When the album was released five years ago, I didn’t know about it. One of my friends, however, had lots of One Direction thoughts and feelings. It’s easy to make fun of boy bands—they’re called boy bands—until you remember that yes, they are boys, and they’re operating in an industry that is notorious for exploiting kids and teenagers. It’s a cruel tradeoff: doing something you love, quite often at the expense of your personal life and mental health.

Harry Styles was received with lukewarm reviews, which is not bad for an album that one critic called “dad-baiting.” Today, Harry Styles is the most obviously interesting ex-1D musician, maybe because the music industry now appears to take him seriously. (It doesn’t hurt when you pull off a cover of “The Chain,” then Stevie Nicks invites you to perform “Landslide” with her.)

In an interview, Styles told Rolling Stone his goal for his debut: "I didn't want to put out my first album and be like, 'He's tried to re-create the Sixties, Seventies, Eighties, Nineties.' Loads of amazing music was written then, but I'm not saying I wish I lived back then. I wanted to do something that sounds like me."

So what sounds like Styles? In the opening of “Woman,” we hear him say, “Should we just search romantic comedies on Netflix and then see what we find?” Then he actually starts singing: I’m selfish, I know. (Two years later, in “To Be So Lonely,” he expanded on the sentiment: I’m just an arrogant son of a bitch who can’t admit that he’s sorry.)

For a song whose primary lyrics are variations of WOMAN! it’s surprisingly compelling.

There are also several tracks that some critics and fans speculate are about his relationships; these feature such lyrics as She’s a good girl, she feels so good (“Carolina”) and Tastes so sweet, looks so real (“Two Ghosts”).

And then there’s “Kiwi,” which has one of my all-time favorite lyrics: When she’s alone, she goes home to a cactus. Straightforward? (She has a cactus.) Sexual? (A scathing commentary on her romantic partner.) It’s an earworm that never resolves itself into meaning, which makes it all the more memorable.

The opening and closing tracks of the album—“Meet Me in the Hallway” and “From the Dining Table”—are, however, contemplative in a way that the other songs seem to avoid on principle. In these two tracks, the relationship Styles writes about is never defined, but I think (project?) that it’s about a friendship and the surreal, dazed grief that follows after one ends without a clear reason.

With “Meet Me in the Hallway,” we see Harry at his lowest:

Just let me know I'll be at the door, at the door

Hoping you'll come around

Just let me know I'll be on the floor, on the floor

Maybe we'll work it out

The rest of the album happens. WOMAN! WOMAN! (hey) (la-la-la-la-la).

Then comes “From the Dining Table”:

We haven't spoke since you went away

Comfortable silence is so overrated

Why won't you ever be the first one to break?

Even my phone misses your call, by the way

During the pandemic, my friend stopped talking to me. There was no grand unified theory of why, just me trying to understand what happened and if she were okay and I love you, are you okay. Saying I’m here and feeling stupid, because what is here: a space where everything is safe so nothing is real?

I miss my friend.

The appeal of returning to albums is, I think, an exercise in self-narrative. Don’t we want to understand how we grew into our current selves? I wish that I knew what I know now, when I was younger, Ronnie Wood sings on “Ooh La La.” I wish that I knew what I know now, when I was stronger.

The people you once were, the people you wanted to become or thought you could: they appear in your house all the time. And as with most houseguests, they’re a mix of delightful and infuriating, some more than others. (There is always someone who does not understand the concept of a trash can.)

“I think we are well advised to keep on nodding terms with the people we used to be, whether we find them attractive company or not,” Joan Didion wrote in Slouching Towards Bethlehem.

Didion’s opening salvo in the essay “The White Album” gets trotted-out so regularly it’s insulting it hasn’t won Best in Show at the Westminster Dog Show. “We tell ourselves stories to live,” she wrote, and thousands of highlighters sprung into action.

But over the next 30-odd pages, Didion relentlessly strips down that line, charting the cultural and political chaos, as well as her own, of the decade following 1968. Stories don’t help you live; they help you live in an air-tight atmosphere, a false one, full of charismatic coincidences. And if something goes wrong? That’s the narrator’s fault.

Didion says otherwise: it’s the narrative that fails, not the narrator. Because a narrative that insists on its own omniscience promises us everything but the truth. “Quite often I reflect…on the fact that Roman Polanski and I are godparents to the same child, but writing has not yet helped me to see what it means,” she wrote.

Of all the tracks on Harry Styles, “From the Dining Table” is the one I return to the most. It lives in its own silence, its unanswered echoes of longing. All we really want from another person is to be heard. The song ends on a resigned note: Why won’t you ever say what you want to say?

Honesty requires gentleness to sustain itself, and we don’t always know how to give that to ourselves. Returning to music we once loved, we invite the possibility of seeing who we once were, now, with the compassion we couldn’t find then. And so the song plays on, hopefully.

With thanks to Vicky Gu and Miel Moreland for their thoughtful edits and feedback. Miel saved me from floating conspiracy theories I absorbed years ago while watching a One Direction truther YouTube series at 3am and muttering, “Yes, this all makes sense!”

Share your small good thing: What’s an album you’ve revisited lately? What does it bring up for you? Or—what was something from your week that brought you joy?

So excited to see more of this! Thank you for starting this up. There are so many albums I need to go back and give a hard listen to through this lens!

honored to be a part of the first (!!) small good thing